The Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This page is currently being maintained for archival purposes only. For the latest information, please visit us here.

Undergrads as hydro-detectives

Professor Rosemary Knight’s students investigated the health and sustainability of their hometown watersheds in Earth Systems 104: The Water Course. Using hydrological principles, the students found many similarities - and some striking differences - among their local water supplies.

By

Miles Traer

<p>Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences</p>

April 1, 2015

Miles Traer

<p>Rosemary Knight (front row at left) and her students listen to freshman Victor Xu (far right) as he discusses his hometown watershed near Indianapolis.</p>

Professor Rosemary Knight stood in front of the classroom and asked her students, “When you turn on the tap at home, do you know where your water comes from?” It was a seemingly simple question, and yet the room of undergraduates spent winter quarter investigating the answer.

The students enrolled in Earth Systems 104: The Water Course came to Stanford from all over North America including Alaska, California, Indiana, Maryland, Texas, and Ontario. The final project was a presentation documenting each student’s hometown watershed. Part of the appeal of the class was the hydrological detective story – where does water enter and leave the system, how healthy is the watershed, and are the local cities, districts, and municipalities managing the watershed sustainably? As the students presented their findings at the end of the class, they pointed out some similarities among watersheds along with some striking differences.

Inputs and outputs

During the class, Knight, the George L. Harrington Professor in the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, taught her students how to construct a simple model, called a box model, to determine whether watersheds were being sustainably managed. The students then researched where and how much water entered and left the watershed. Ideally, more water entered the box than left it.

Some sources were familiar, such as surface water streams and lakes in central Indiana or groundwater aquifers in Texas. Some sources were less familiar, like desalinization plants or rainwater storage cisterns in southern California.

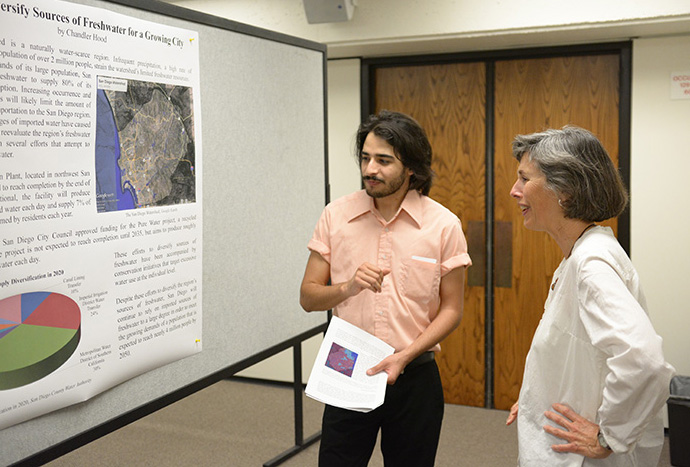

Still other watersheds highlighted how humans move water to suit growing needs. During his presentation, senior Chandler Hood pointed out that his hometown near San Diego, CA imported most of its water. Sophomore Rachael Stryer learned that the middle Potomac Catoctin watershed in central Maryland would be managed sustainably if not for the fact that it exported water to a land area twice the size of the watershed itself.

Professor Rosemary Knight (right) talks with senior Chandler Hood about the inputs and outputs to his hometown watershed near San Diego, CA.

In those watersheds where the rate of water removal exceeded the rate of water entering, the students calculated the estimated time until the system dried up. In some cases, like central Indiana, the water in the watershed would not be depleted for hundreds of years. In others, like eastern Texas, the watershed could dry up in just seven years if management practices don’t change. With these simple calculations, the students gained a different perspective on the sustainability of their water supply.

Health and side effects

Just because a watershed is sustainably managed in terms of water quantity doesn’t necessarily mean that it produces healthy water. Freshman Kathryn Treder found that her watershed near Anchorage, AK was sustainably managed, but the water contained higher than acceptable levels of manganese, an element that can impair intellectual development in humans.

Freshman Victor Xu discovered that the water system surrounding Indianapolis, IN could potentially last for hundreds of years, yet contained higher than normal levels of arsenic and even cyanide. “When I started, I thought that our watershed would be sustainable. But I didn’t think it would have things like cyanide in it,” said Xu.

Health effects weren’t the only considerations for the students. Junior Katelin Lin investigated the Buffalo-San Jacinto watershed in east Texas and reported that water was being pumped out of the ground so rapidly that the land above was subsiding.

Senior Jaye Buchbinder investigated her hometown watershed near Los Angeles, CA that runs up alongside the Pacific Ocean. She discovered that as managers pumped out fresh water, saltwater from the nearby ocean moved inland and infiltrated the aquifer in a process known as saltwater intrusion. The saltier the water gets, the less useful it is.

As the students presented their research, a common observation was that the risks to water systems are often invisible to the public.

Where does your water come from?

On a Thursday evening during finals week, the students of Earth Systems 104 walked around the room to look at the series of posters explaining what they had discovered about their watersheds. As they chatted, they nibbled on pizza and shared the most surprising facts they learned during their research.

The mood was upbeat and the students all seemed to be optimistic now that they knew more about where their water came from, despite some of the details regarding sustainability and water health. The students had their own reasons for optimism, yet Jaye Buchbinder seemed to best sum it up, “It feels good to be a well-educated citizen.”