The Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This page is currently being maintained for archival purposes only. For the latest information, please visit us here.

Stanford scientists react to quakes in Japan and Ecuador

Geophysicists say the earthquakes are a tragic reminder that monitoring less active faults is vital for accurate hazards assessments.

By

Miles Traer

<p>Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences</p>

April 15, 2016

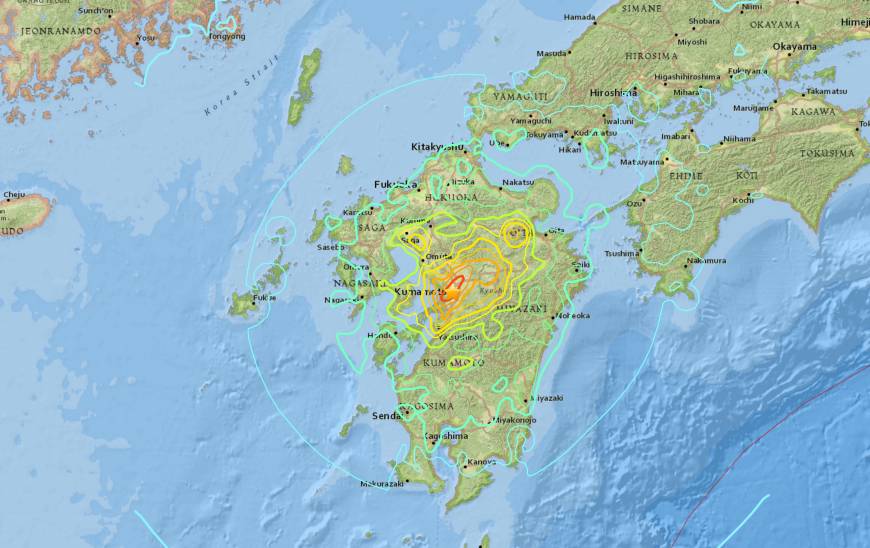

<p>Credit: USGS</p>

At 1:30 a.m. local time, a large magnitude-7.0 earthquake struck the southwestern corner of Japan, one day after the area had already suffered death and destruction in a pair of magnitude 6 foreshocks.

“Tragically, events like this aren’t rare in this part of the world,” said geophysicist Greg Beroza, the Wayne Loel Professor at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences. “Japan has crustal earthquakes that happen almost everywhere. As a result, they have this distributed hazard across the entire country.”

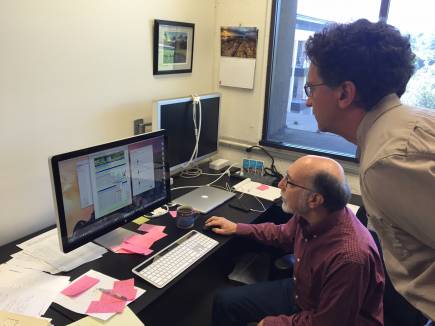

Geophysicists Greg Beroza (right) and Bill Ellsworth look over the acceleration data from this morning’s magnitude-7.0 earthquake in southwestern Japan. Credit: Miles Traer

Early news reports indicate additional fatalities can be expected in addition to nine deaths in the foreshocks. The U.S. Geological Survey estimates roughly one-to ten-billion dollars in damages. But the final figures could be much higher, said Stanford geophysics professor, Simon Klemperer.

“This quake is similar to to the magnitude 6.8 Kobe earthquake in 1995 that was roughly the same size,” Klemperer said.

Unlike the massive magnitude-9.0 Tohoku earthquake in 2011 where the fault was located at sea and far from land, the April 16 quake occurred at shallow depth directly beneath heavily populated areas.

“We get the same kinds of strike-slip earthquakes in Northern California on the San Andreas and Hayward faults,” Klemperer said. “The Japan quake is a wake-up call.”

This latest quake appears to have occurred on the the Futagawa-Hinagu fault zone, which has been well studied by scientists.

“That fault system that broke in this earthquake is part of the Japanese hazard model,” said Bill Ellsworth, Stanford Earth professor (research) of geophysics. “So this earthquake helps validate the approach that’s being used in both Japan and the United States to evaluate earthquake hazard, even though the fault might not have moved in historical times. Dormant faults, such as the one that rocked Napa in 2014 can clearly be dangerous.”

Hours after the Japanese earthquake, another major quake struck Ecuador, 9,000 miles away. The magnitude-7.8 quake was centered beneath the village of Muisne and has killed more than 400 people. Despite occurring on the same day, scientists say the two events are not related: the quake in Ecaudor was a metathrust event, in which a tectonic plate slides under, or "subducts", beneath another, and not a strike-slip fault like the Japanese quake.

In both cases, however, quake damage was extensive, Ellsworth said. "Both epicentral areas suffered severe damage to buildings with poor seismic design, as did many lifeline systems," he added. "A major challenge survivors in both areas face will be the long road to recovery. This is why resilience needs to be a key component of earthquake preparedness, along with knowing what to do before and during a quake."