The Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This page is currently being maintained for archival purposes only. For the latest information, please visit us here.

Stanford Earth’s Rob Jackson urges community to convey the multiple benefits of climate action

Rather than talk about the negative things, point to the co-benefits of finding climate solutions – from economics and jobs to water and the air we breathe.

By

Danielle Torrent Tucker

February 28, 2017

<p>A child wears a mouth mask for protection against air pollution in Beijing. Credit: Hung Chung Chih (Shutterstock)</p>

When it comes to climate change, science-based facts prove the looming problem is real. But to gain broader understanding among skeptics and the general public, advocates should refocus their conversations on the positive outcomes of climate action, says Rob Jackson.

“What people care most about are health and safety,” said Jackson, the Michelle and Kevin Douglas Provostial Professor at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). “These factors motivate people more than the greenhouse gas question.”

Jackson delivered a comprehensive talk Jan. 25 titled How Cutting Greenhouse Gas Emissions Improves Our Water, Air, and Health, as part of the Earth Matters lecture series co-sponsored by Stanford Continuing Studies and Stanford Earth. About 60 people attended the lecture, including community members, students, and Stanford faculty.

Beginning with the history of climate science, Jackson discussed a wide variety of research in the field, including global warming predictions, the impacts of fracking, and how policy changes have curtailed methane leakage.

“Well over 100 years ago, people had already made the link from burning fossil fuels to changes in the Earth’s atmosphere,” Jackson said. “They understood the basic physics, and the basic physics has not changed since then.”

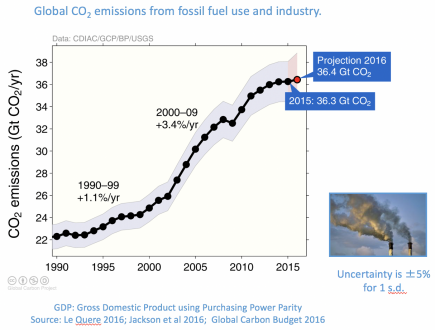

There is “no uncertainty that the Earth is warming” and it has been 40 years since we have experienced a cooler-than-average year, said Jackson, who chairs the Global Carbon Project, an initiative that places fossil fuel emissions in the context of natural carbon dioxide sources like deforestation and ocean uptake and release. To explain the concept of cumulative emissions, Jackson described the atmosphere as a bucket that can hold only a certain amount of CO2 before a given temperature increase occurs.

Analyses of cumulative emissions show people generated about 500 billion tons of CO2 through 1960, and that number has increased to about 2,000 billion tons today. Presenting a graph of current global fossil fuel emissions, Jackson reflected on some positive aspects of current trends: Fossil fuel emissions have been stable for the past three years. Previously, lower CO2 emissions only occurred when the economy shrank, he said.

Click the image above to view Jackson's talk on Facebook Live.

“Emissions are flat; that’s the good news,” Jackson said. “The bad news is they’re flat at a record level … it’s not anywhere near where we need to be. We have a lot of work still to do.”

If U.S. emissions continue to decline at the current rate, the country would only reach about 40 percent of its commitments in the 2015 Paris Agreement. “But they are declining and we can’t lose sight of that,” said Jackson, who recently published metrics to track the emissions levels of all countries in the Paris Agreement against their commitments.

Jackson emphasized the imperative to produce renewable energy, but said the most important step society can take to reduce emissions in the immediate future is to eliminate coal production.

“Fossil fuel use kills people,” Jackson said. Most of the fossil-fuel-related deaths are associated with coal pollution. “There are 3 to 6 million people who die each year from air pollution around the world.”

Jackson discussed the controversies of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, the potential danger of contamination to freshwater aquifers, and the importance of mineral or subsurface rights to property owners. Despite these divisive issues, natural gas can be a viable short-term alternative, since it generates less than 90 percent of the sulfur dioxide and much less particulate matter than coal.

Methane and other leakage from oil and natural gas operations – another concern for health and safety – is especially prevalent in legacy oil wells, according to Jackson’s research.

“By fixing old and new infrastructure and tightening down the natural gas supply chain, we can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and climate change,” Jackson said. “It will make the system safer and save us money, too.”

In another study, Jackson’s team and colleagues published the first publicly available maps of natural gas leaks in cities. Measuring 800 miles of Boston block by block, the research identified 3,400 leaks and isolated the No. 1 predictor of a leak as old cast-iron pipes. The work led to policy reform in Massachusetts, he said.

Jackson looked beyond pollution to explain how energy production impacts the ecosystem in unexpected ways. While the top consumptive use of water in the U.S. is to irrigate agriculture, about 40 percent of the water withdrawn from our waterways is used to cool power plants. Different energy production methods have distinct water demands – and fracking uses less water than coal or nuclear energy, he said.

Through his detailed depiction of the Earth from the eyes of an Earth scientist, Jackson reflected a constant hope that communication about the economy, air pollution, human health, water, and safety will reach everyone.

“It’s our job, our responsibility to talk about the way the world is, to give our best information of what we think will happen,” Jackson said. “I’m an optimist at heart – you have to be an optimist to work in this business. And keep fighting the fight.”

Jackson is also a senior fellow at the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment and the Precourt Institute for Energy.