The Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This page is currently being maintained for archival purposes only. For the latest information, please visit us here.

"Seeing" Water Underground

New imaging tools developed by Stanford Earth scientists could soon inform more proactive strategies for groundwater management.

Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences

June 9, 2015

Pink Sherbet Photography

The Stanford team found ways to visualize underground water sources using innovative technologies.

Professors Rosemary Knight and Howard Zebker

Many communities, especially in arid environments, meet the water needs of residents and farmers by pumping from subsurface aquifers. But until now, the only way for water managers to gather crucial information about the changing state of the water table was to drill monitoring wells—an invasive and expensive practice that at best yielded only "snapshots" of information limited to the area around each well.

This lack of water-level data has sometimes led to poor management and the rapid depletion of underground reservoirs. And worse. Pumping freshwater out of the ground changes the fluid pressure of underground aquifers. If an aquifer is located near the coast, overpumping can result in an influx of saltwater.

This phenomenon poses a particular threat in dry California—especially along the agriculturally productive Monterey and Santa Cruz coasts, and especially in times of drought like the one facing the region now.

"During a drought, there is less precipitation, so the natural recharge of the aquifer does not occur," says Stanford geophysicist Rosemary Knight, the George L. Harrington Professor in the School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences. "At any time, it's a balancing act between the amount of water that goes into the aquifer and the amount that comes out."

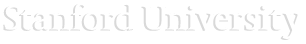

Pidlisecky, Moran, Hansen, and Knight, In review for the journal Groundwater

An ERT map of the underground saltwater-freshwater interface along the coast between Marina and Seaside, California.

Knight is an expert in adapting geophysical technologies to study groundwater resources and aid in their management. In late 2014, she and her team partnered with her former student Adam Pidlisecky, now an assistant professor of geosciences at the University of Calgary, and engineering company WorleyParsons to conduct an ambitious scientific survey. They used an advanced geophysical imaging technique called electrical resistivity tomography (ERT) to map the salinity of aquifers along the entire Monterey Bay coastline to a depth of up to 1,000 feet. The technique capitalizes on the fact that saltwater and freshwater have different electrical conductivities.

Courtesy of Jess Reeves

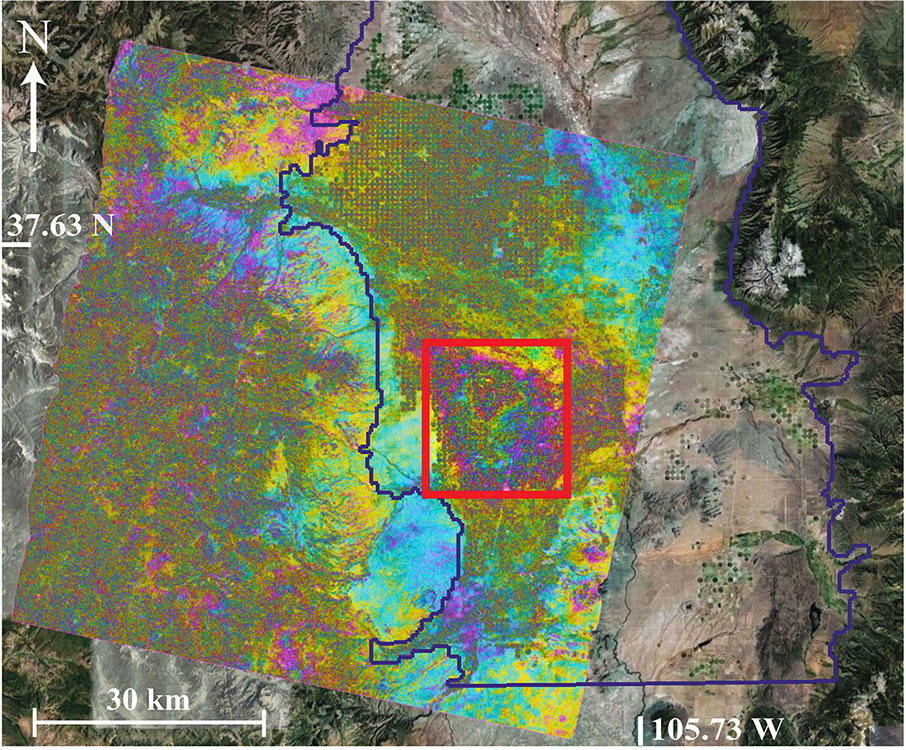

InSAR image of the San Luis Valley in Colorado

The team's findings, which are expected to be available later this year, could help refine computer models of saltwater intrusion in the region and foster new ways of thinking about groundwater management along the Monterey Bay coastline—and beyond.

Kim Anderson, general manager for the region’s Soquel Creek Water District, is already anticipating how she will use the team’s data. "We don’t know how soon saltwater will hit our production wells, because we don’t know where the interface is between the saltwater and the freshwater," she says. "Once we know that, we can predict how much time we have to address the situation and make sure it doesn't migrate into our production wells."

Moving up for a Better View

Knight has also teamed up with her Stanford colleague Howard Zebker, a professor of both geophysics and electrical engineering, to track changes in groundwater systems from space.

Zebker was an early pioneer in the use of Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR) to map out deformations associated with tectonic processes such as earthquakes and volcanoes.

Combining their expertise to use an established technique in a new way, Knight and Zebker are using satellite data of tiny vertical shifts in ground movements to monitor changes in the amount of underground water, exploiting the fact that the ground surface moves up and down as water moves into and is then pumped out of the underlying rock.

"I knew nothing about InSAR," admits Knight. A talk she happened to attend on the technique made her see its potential for helping monitor seasonal changes in aquifer water levels.

"When fully developed for this purpose, InSAR could revolutionize the management of groundwater worldwide by allowing water managers to efficiently gather high-quality information about groundwater levels across vast areas," she says.

The scientists are currently testing the technique in California's Central Valley, where extensive groundwater pumping has led to subsidence—or sinking—of land, which could affect the structures sitting on top.

Of course, Knight is also interested in the really big picture.

"We also want to learn more about the groundwater system in the region," she says. "So we are trying to integrate the InSAR data with other hydrologic data to calculate the total loss of groundwater storage, and gather information about water level changes in the aquifers over large spatial and temporal scales."