The Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This page is currently being maintained for archival purposes only. For the latest information, please visit us here.

Number of manmade earthquakes in Oklahoma declining, but risk remains high

Stanford scientists predict that over the next few years, the rate of earthquakes induced by wastewater injection in Oklahoma will decrease significantly. But the potential for damaging earthquakes will remain high.

By

Ker Than

November 30, 2016

Clusters of earthquakes in Oklahoma have been linked to wastewater injection from oil and gas drilling. (Image credit: bashta / Getty Images)

The number of manmade, or “induced,” earthquakes in Oklahoma has risen dramatically since 2009, due largely to wastewater amassed during oil and gas recovery operations being injected deep underground into seismically active areas.

But new state regulations that call for reductions in wastewater injection should significantly decrease the rate of induced earthquakes in Oklahoma in the coming years, Stanford scientists say.

“Over the past few years, Oklahoma tried a number of measures aimed at reducing the rising number of induced quakes in the state, but none of those actions were effective,” said Mark Zoback, the Benjamin M. Page Professor at Stanford’s School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences.

While wastewater produced during oil and gas drilling has been disposed of by underground injection in this area for many decades, induced seismicity was not a problem until the volumes being injected were massively increased, beginning around 2009. In the past six years, billions of barrels of wastewater were injected into the Arbuckle formation, a highly permeable rock unit sitting directly atop billion-year-old rocks containing numerous faults.

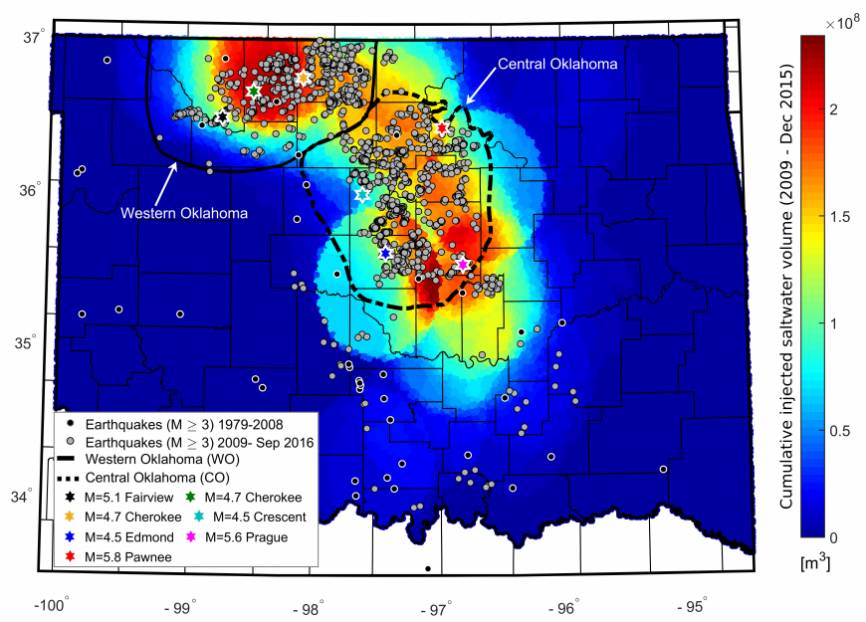

Research by Zoback and his graduate student Rall Walsh published last year established the correlation in space and time between the areas where the massive injection was occurring and the induced earthquakes. The pair showed how pressure buildup resulting from the wastewater injection can spread over large areas and trigger earthquakes tens of miles from the injection wells.

In light of these findings, the state’s public utilities commission – the Oklahoma Corporation Commission – last spring called for a 40 percent reduction in the volume of wastewater being injected. The bulk of that wastewater comes from oil production in several water-bearing rock formations that had not been extensively drilled until a few years ago.

A new physics-based statistical model developed by Stanford postdoctoral fellow Cornelius Langenbruch and Zoback, detailed online this week in the journal Science Advances, predicts that the continued reduction of injected wastewater will lead to a significant decline in the rate of widely felt earthquakes – defined as quakes measuring magnitude 3.0 or above – and a return to the historic background level in about five years.

Saltwater disposal and earthquakes in Oklahoma. Image courtesy of Cornelius Langenbruch.

When the volume of wastewater injection peaked in 2015, Oklahoma was experiencing two or more magnitude 3.0 earthquakes per day. Before 2009, when wastewater injection really started ramping up, the rate was about one per year.

“Several months after wastewater injection began decreasing in mid-2015, the earthquake rate started to decline,” Langenbruch said. “There is no question that there is a significantly lower seismicity rate than there was a year ago.”

Unfortunately, even though the rate of induced quakes will continue declining, the probability of potentially damaging earthquakes like the magnitude 5.8 earthquake that struck the town of Pawnee in September — the largest recorded earthquake to strike Oklahoma — will remain elevated for a number of years, the Stanford scientists say.

“As long as elevated pressure persists throughout this region,” Zoback said, “there will be an increased risk of triggering damaging earthquakes.”

Mark Zoback is also a senior fellow at Stanford’s Precourt Institute for Energy, an affiliate of the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment, and the director of the Stanford Natural Gas Initiative. Funding for this study was provided by the Stanford Center for Induced and Triggered Seismicity.