The Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This page is currently being maintained for archival purposes only. For the latest information, please visit us here.

Crossing the financial “Valley of Death” to clean energy

Stanford’s Dan Reicher and Alicia Seiger identify key strategies to catalyze investment in clean energy resources.

By

Miles Traer

Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences

October 29, 2015

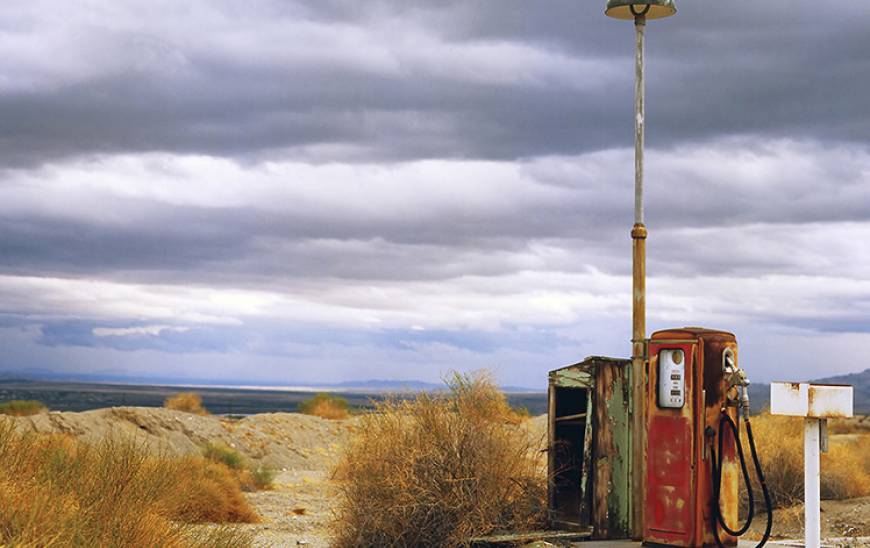

Shutterstock

With global energy consumption rising exponentially, scientists, lawyers, and financial experts all over the world are teaming up to find ways to expand energy production while minimizing the impacts on the atmosphere and environment. At Stanford’s Global Climate and Energy Project (GCEP) Research Symposium October 13, Dan Reicher and Alicia Seiger told a crowd of hundreds, “By the year 2030, we need to increase clean energy investment to one-trillion-dollars per year to combat climate change.” They proceeded to explain how to finance such a daunting task.

“We need a lot of money spread across a complicated spectrum of solutions that will likely span decades,” said Reicher, the executive director of Stanford’s Steyer-Taylor Center for Energy Policy and Finance. “There are two big challenges as we move clean energy technologies out of the lab to full-scale deployment. One is innovation, taking ideas out of the lab and proving that the idea works at a small scale. The second is commercialization, scaling up the technology to full-sized deployment. We call these the ‘valleys of death.’”

Dan Reicher (left) executive director of Stanford’s Steyer-Taylor Center for Energy Policy and Finance, and Alicia Seiger, deputy director of the Steyer-Taylor Center (credit: Mark Shwartz).

The sardonic nickname seemed to become more and more appropriate as Reicher and Seiger showed example after example of cleaner energy technologies taking decades to move from the lab to full-scale deployment, if they made it that far at all. Even a technology like hydraulically fracturing bedrock to access natural gas reserves, which has seen wide deployment throughout the US and the rest of the world, took 65 years to cross the financial valley of death, Reicher said.

According to Reicher, there are lessons to be learned from the expansion of oil and gas projects. “One of the most obvious solutions that we found is to give renewable energy initiatives the same access to finance sources as those used to fund large-scale oil and gas pipeline projects,” he said.

One approach is to provide clean energy projects access to the tax benefits and low financing costs of master limited partnerships (MLPs). Said Reicher, “Curiously, when the law was passed to authorize MLPs in the early 1980s, it explicitly excluded renewables. We asked ourselves why that should be?” In response, Reicher helped develop and advance pending legislation in Congress to expand MLP availability to renewable energy and other clean energy sources.

Another potential solution involves financing more costly projects to pull carbon dioxide out of the emissions from power plants and industrial facilities and bury it deep underground, a process called carbon capture and storage (CCS). “We really need to be using CCS for coal, natural gas, and a whole host of industrial carbon sources. But the costs are too high,” Reicher said.

Nonetheless there is promise in new financial solutions that can be found in approaches that were used decades ago to cut the cost of new technologies. As Reicher explained, a financing tool called Private Activity Bonds (PABs) was used to fund projects deploying advanced technologies to clean up the smog covering Los Angeles and other cities in the 1970s and 1980s. However the authority for PABs for air pollution control projects expired in the 1980s. “The Private Activity Bonds that were used to clean up power plants decades ago could be used today for CCS,” said Reicher. “We just need Congress to expand power plants’ access to these bonds.”

As Reicher and Seiger stated multiple times during their presentation, financing a clean energy future remains a daunting task. But thanks to the prospect of potential new financial constructs, the valley of death may start to look a little more hospitable.