| Search | | People | | Calendar | | Internal Resources | | Home |

Crustal Deformation and Fault Mechanics |

|

|

|||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

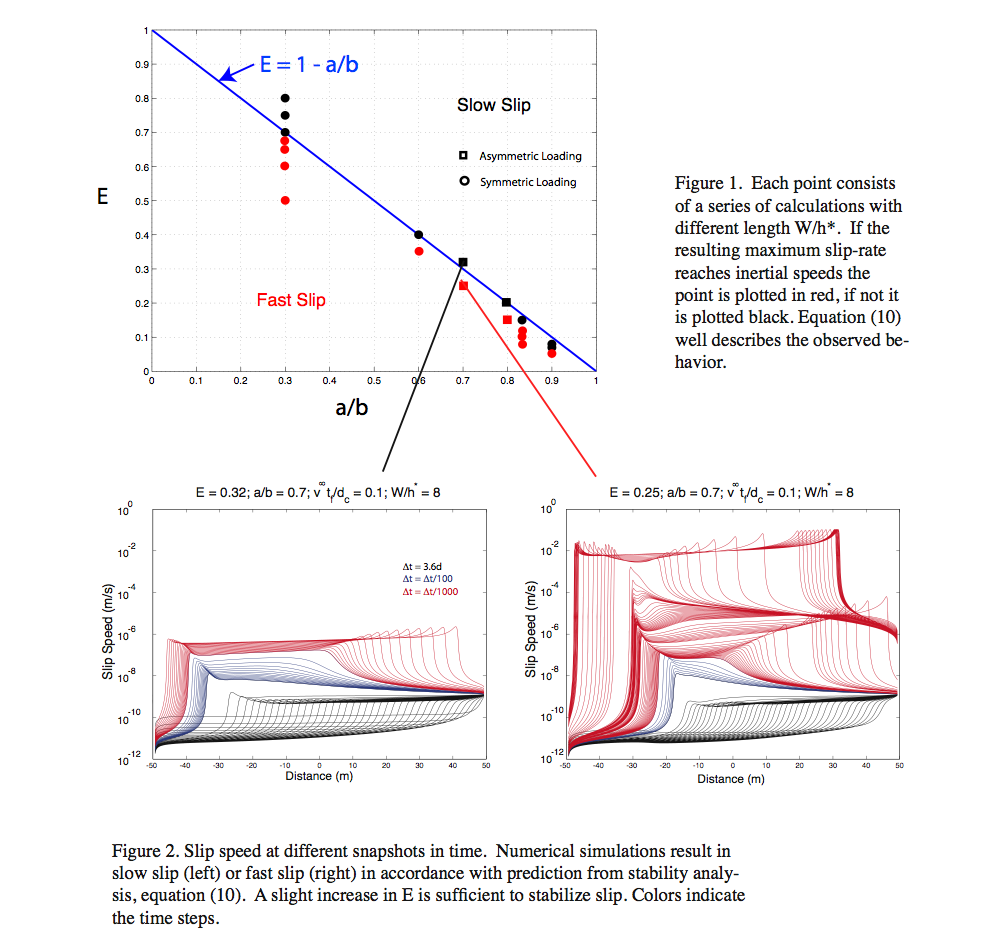

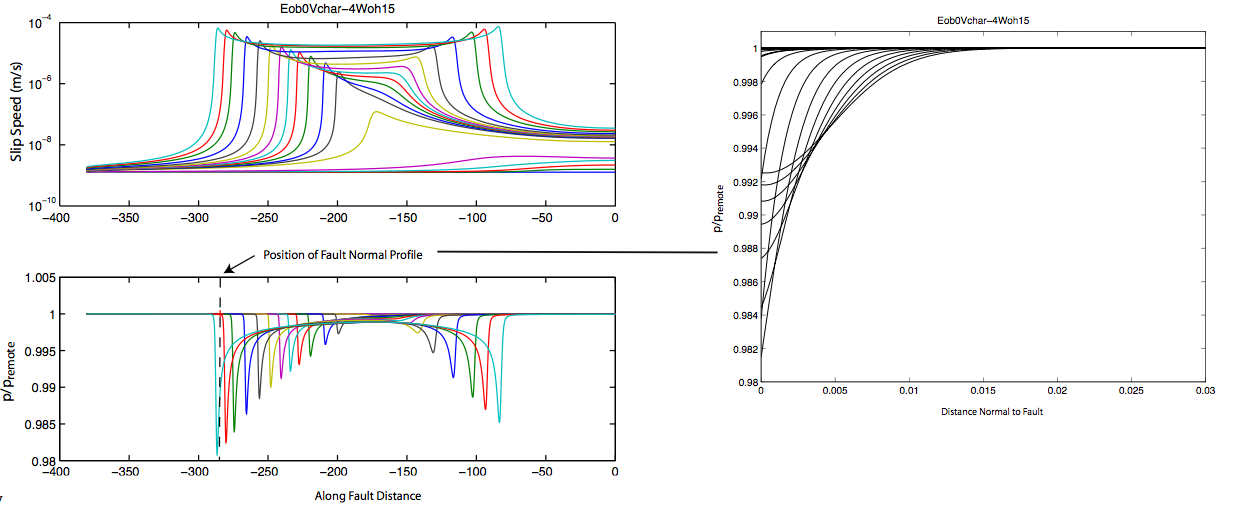

Slow Slip in Locked Subduction ZonesOne of the most exciting discoveries in recent decades has been the recognition that many subduction zones undergo transient slip events at depths below the locked mega-thrust zone. These slow slip events, or silent earthquakes, have been detected by GPS networks in Cascadia, southwest Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, and Alaska. We have also discovered slow slip events beneath Kilauea volcano in Hawaii. In subduction zones transient slip is often, but apparently not always, accompanied by non-volcanic tremor. The minimum dimensions of slow slip zones are typically several tens of kilometers; slip per event is small (on the order of 2 cm in Cascadia) indicative of low stress drops; and average slip velocities are roughly one to two orders of magnitude above the plate velocity (2 cm/10 days or 10^-8 m/s in Cascadia). Slow slip events in Cascadia propagate along strike at rupture speeds of roughly 10 km/day, while others such as Tokai slow event slip for several years in largely the same locality. Understanding the physics of slow slip events and how they differ from normal, fast earthquakes is one of the most pressing current challenges in seismology. Understanding what causes some events to slip slowly compared to others that slip rapidly, radiating damaging seismic waves would provide a fundamental insight into how earthquakes work. The societal importance is that every slow slip event adds stress to the adjacent locked megathrust zone bringing it closer to failure. For this reason we are very interested in the triggered earthquakes that occur in Hawaii, Japan, and New Zealand. We have been exploring the possibility that dilatant strengthening may provide a reasonable explanation for slow slip events. Dilatancy is the tendency for the pore space in granular materials to expand during shear. The increased pore-space will drop the fluid pressure within the fault zone, increasing fault strength according to the effective stress principal, unless pore-fluid can flow into the fault zone fast enough to keep up with the rate of dilatancy. Our hypothesis is that frictional weakening allows slip to nucleate, but that as the slip-rate increases fluid flow becomes increasingly unable to keep up with the rate of dilatancy. Depending on the constitutive parameters and the ambient effective normal stress, dilatancy can quench the instability resulting in a slow slip event. Our approach has been to use numerical modeling and theoretical analysis to understand the conditions when dilatancy stabilizes fault slip. This involves coupling the equations of elasticity, rate-and state dependent friction laws, to fluid transport equations, generating a large system of coupled partial differential equations. In some work we have approximated the fluid diffusion equations with a “membrane diffusion approximation” which is appropriate if there is a low permeability zone bordering the fault. Under this approximation we have been able to predict when ruptures will be fast or slow, depending only on two dimensionless parameters. One (E) measures dilatancy relative to frictional weakening, the second (a/b) measures the direct velocity strengthening vs. frictional weakening in the rate state friction law (low a/b is more unstable, a/b=1 is neutrally stable).  In ongoing work we are extending this to a more complete description of fluid flow using the Finite Difference Method to solve the pore-pressure diffusion equation. We find that given sufficiently low permeability of the surrounding rock that dilatancy is sufficient to stabilize slip against inertial instability. Future work will involve coupling the modeling of dilatancy to our ongoing analysis of thermal pressurization. Slip generates frictional heat, which acts to increase pore-pressure, potentially destabilizing the fault. We hypothesize that what may ultimately control whether slip is fast or slow is the competition between thermal weakening and dilatant strengthening.  Figure 3: Numerical slow-slip event with dilatancy and Finite Difference computation of fluid transport. top left) Log slip-rate as a function of distance along fault at different snapshots in time. Bottom left) pore-pressure normalized by remote pore-pressure at different snapshots in time. Note the strong reduction in pore-pressure associated with the propagating rupture front. Right) Normalized pore-pressure as a function of distance normal to fault. Note pore-pressure is drawn down as rupture front approaches, and then recovers as the front passes. |

| Last modified

Please contact the webmaster with suggestions or comments. |

|