SUPRI-D Research Projects

Analyzing Temperature Transients Using Permanent Downhole Temperature Data

Obinna Duru, MS candidate

1. Motivation

Permanent Download Gauges (PDG) have been deployed extensively over the last decade to provide a continuous source of downhole pressure and temperature data, and thus also providing a record of spatial and temporal reservoir information during different production scenarios (constant and transient production periods).

Over the years, in the development of pressure transient analytical techniques, it has been common to assume isothermal conditions. In addition, it has been common to assume uniform temperature in the reservoir and production zone during fluid flow through the well bore. However, measurements of temperature behavior at a finer scale have shown some response of the temperature distribution to changes in flow conditions in both the reservoir and the production zone, in space and time.

This work aims at identifying the underlying physical phenomena responsible for these temperature transients and possible ways to use the findings in reservoir description, parameter estimation and evaluation of well performance.

2. Introduction

When oil and/or gas flows from a reservoir, through the wellbore to the surface, the fluid temperature changes. Several factors may be responsible for this, and they include heat loss to the surrounding formation through conduction, and thermodynamic behavior such as the Joule-Thomson effect, adiabatic expansion effects and heating due to friction between the flowing fluid and the rock matrix in the reservoir. Several authors studied the thermodynamics of flow through porous media, especially in the context of heat convection and conduction.

Ramey (1962) developed a model for the prediction of wellbore fluid temperature as a function of depth and production time, for injection wells. Shiu and Beggs (1980) modified Ramey’s model to predict the wellbore temperature profile for producing wells, where the temperature of fluid entering the wellbore from the reservoir is known.

Sagar, et al. (1991), developed a complex model for wellbore temperature distribution that accounted for kinetic energy and Joule-Thomson effect due to heating/cooling caused by pressure changes within the fluid during flow.

Haassan and Kabir (2002, 2005) presented a model that incorporated the hydrodynamics of different flow patterns and well geometry.

Valiullin et al., Sharafutdinov (2001) and Filippov et al. (1999) considered flow through the porous reservoir and defined models for the thermal variations.

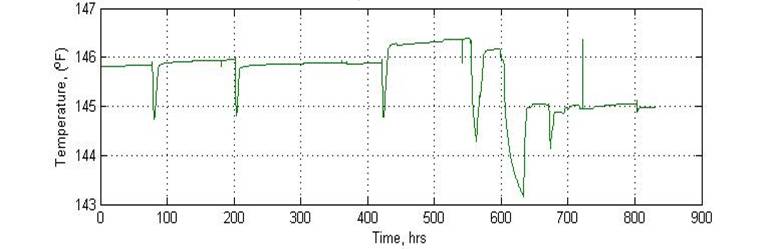

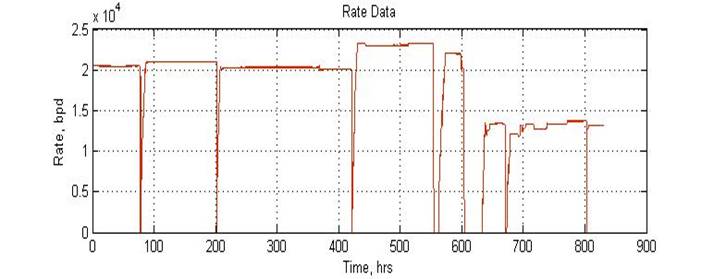

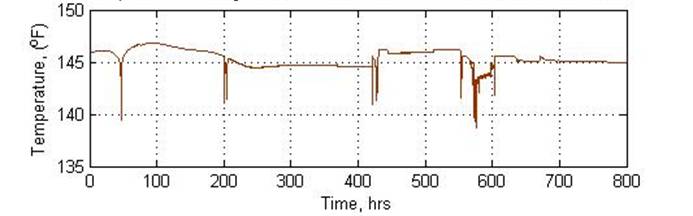

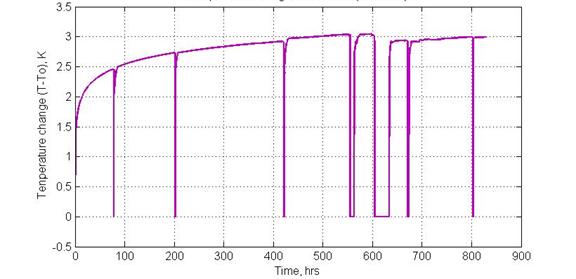

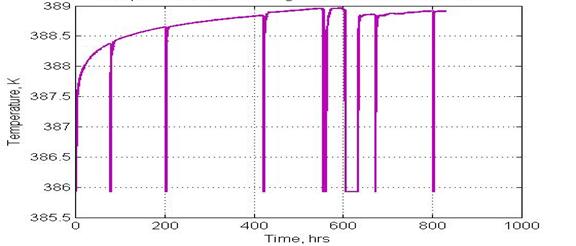

Figure 1 shows an example of measrements of the response of temperature to changes in flow behavior, while Figure 2 is the flow rate plot. Both data sets have been preprocessed to remove major outliners obviously due to gauges.

Figure 1: Temperature measurements from a permanent downhole gauge.

Figure 2: Rate measurements from a permanent downhole gauge (at the same location as temperature measurements shown in Figure 1).

3. Research Results So Far

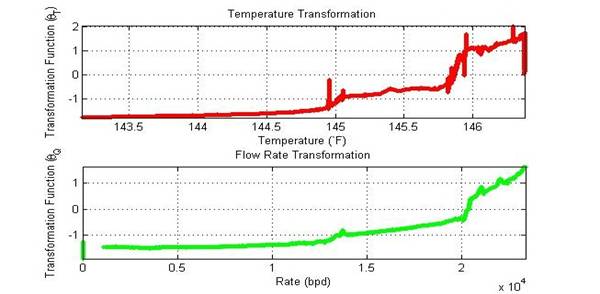

In order to ascertain the dependence of the temperature transient behavior on other flow parameters such as rate, time and pressure, nonparametric regression analysis was applied to the data from field measurements. Specifically two nonparametric multiple regression methods – Alternating Conditional Expectation (ACE ) algorithm of Breiman and Friedman (1985) and the Additivity and Variance Stabilization (AVAS) algorithm of Tibshirani (1988) -- were applied to the data set, to estimate optimal transformations that will result in maximum correlation between a dependent response variable (temperature) and multiple independent predictor variables (rate and time).

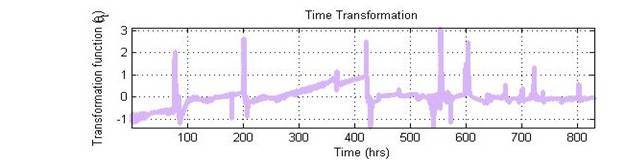

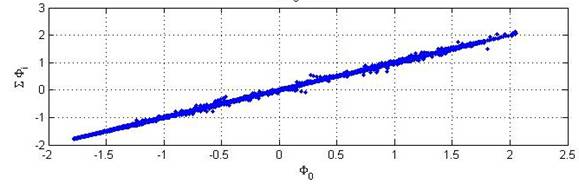

Figures 3 and 4 show the optimal transformations of the three variables, while Figure 5 shows the correlation between the transformations. As seen from the regression on the transformation, a strong functional relationship exists between flow rate and time (predictors), and temperature (response variable).

Figure 3: Temperature and rate transformation functions.

Figure 4: Time transformation.

Figure 5: Correlation of the transformations.

In the light of this functional relationship, it is clear that measurements of temperature show a dependence on flow rate. Therefore, an attempt was made to develop general models for the temperature dependence on rate and time. Later, more specific models for the transient periods will be developed.

Two simplified models were developed:

- A model from a regression on the transformations by using curve fitting tools.

- A model from the physics and thermodynamics of the flow system.

Model 1:

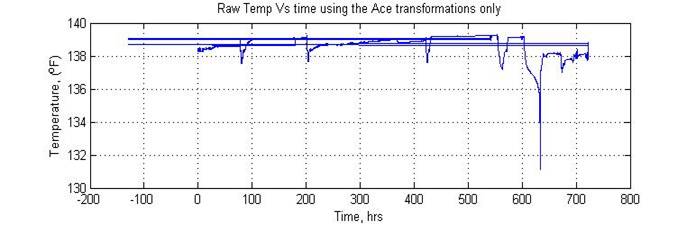

Figures 6 and 7 show a crude reproduction of the temperature plot, but this time from the two different models developed from fitted curves on the transformation functions. For Figure 6 the filtered (preprocessed temperature data) were used in ACE while for Figure 7, the raw unfiltered temperature data were used, to generate the transformations that yielded the models.

Figure 6: ACE transformation temperature with filtered data.

Figure 7: ACE transformation temperature with unfiltered data.

These models leave room for further improvements, one of which will be a reapplication of ACE and/or AVAS on the transformations to obtain a further second tier functional relationship before the curve fitting regression. These will be done as part of the further work in this research.

However, the crude replication of the original plot shows some promise which is motivating further work in this regard.

Model 2:

A model based on the physics of the flow process was derived and tested. Essentially, we used the Shiu and Beggs (1980) wellbore temperature model for a producing well, where the inflow temperature into the wellbore from the reservoir was estimated from a model developed for nonisothermal flow in porous media.

Figure 8 is a schematics of the two regions modeled.

Figure 8: Schematics of flow system.

The equation for porous media heat transport was obtained by carrying out a detailed energy balance on a cross-section of the reservoir formation. This model combines the effects of conduction, convection, compressibility (Joule-Thomson and adiabatic expansion) and frictional heating. For simplicity at this stage, the model will be used for a single phase fluid, in a horizontal reservoir with no gravity effects. In a one-dimensional radial coordinate system, in dimensional terms the equation takes the form:

![]()

With associated equations:

Mass Balance:

![]()

Darcy's Law:

![]()

The equation for the wellbore flow, according to Shiu and Beggs (1980) is:

![]()

Equation 1.1 is a convection-advection equation with a source term, and thus comes with the associated difficulty of obtaining an analytical solution for these kinds of equations. An approximate analytical solution and a numerical solution will be sought later for Equation 1.1. However, in order to ascertain the dependence of the temperature on some reservoir parameters, some simplifications were made, as follows.

A homogenous reservoir with low porosity, containing single-phase, undersaturated oil was considered, with negligible diffusion also assumed during flow.

The solutions obtained for temperature at ![]() were:

were:

and

and

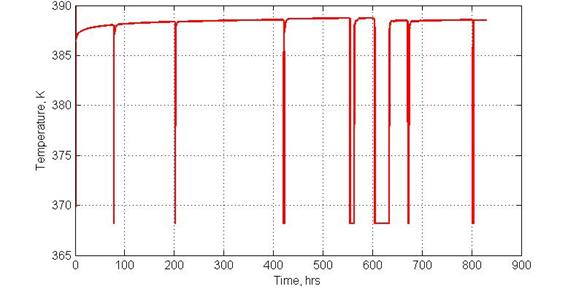

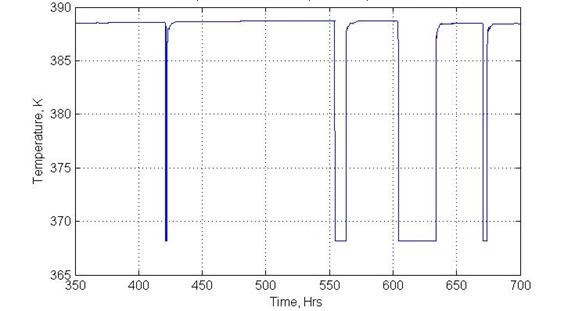

Figures 9, 10, 11 and 12 show the calculated temperature plots after these simplifications:

Figure 9: Temperature change in the reservoir, computed at the wellbore radius.

Figure 10: Calculated temperature of fluid entering the wellbore.

Figure 11: Calculated temperature further up the wellbore at the location of the permanent downhole gauge.

Figure 12; Expanded view of computed temperature.

4. Discussion and Future Research Plans

The model results show some trends that are consistent with the expected temperature transient behavior. The behavior starts with an initial flow (model assumed flowrate was initially at zero, and rose instantaneously to 20000 bpd at start of the test) which lead to a temperature increase before stabilization, and a decline during well shut-in. The effect of the absence of the thermal diffusivity term (assumption of negligible thermal diffusion in the solution) can also be seen in the temperature behavior especially at very low or zero flow rates (little or zero convection).

Future research plans in this work include the following:

- To establish a representative model from the ACE and AVAS transformations on temperature, rate and time.

- To find out if the models from the regression in (i) are universally applicable to all reservoir configurations, or are reservoir-specific. If the models are reservoir-specific, to determine which reservoir parameters affect them.

- For an inverse problem, provide a way for flowrate reconstruction from temperature variation with time and compare with other flow reconstruction methods in the literature.

- Seek other approximate analytical solutions to the physical model, to ascertain the dependence of temperature transients on other reservoir parameters.

- Apply the physical model to multiphase flows.

- Develop numerical solutions to the physical models.

- Compare the physical model with the model from regression on the data, and in the case of a good match, develop a semiparametric algorithm for approximating flow rates using temperature data from permanent downhole gauges.

Nomenclature

References:

Alves, I.N. Alhanati and Shiham, U.: “A Unified Model for Predicting Flowing Temperature Distribution in Wellbores and Pipelines", SPE 20632.

Hasan, A.R. and Kabir, C.S.: “Fluid Flow and Heat Transfer in Wellbores", Society of Petroleum Engineers, 2002.

Izgec, B., Kabir, C.S., Zhu, D., Hasan, A.R.: (2006): Transient Fluid and Heat Flow Modeling in Coupled Wellbore/Reservoir Systems. Paper SPE 102070 presented at the SPE Annual Technical conference, San Antonio, Texas, 24-27th Sept.

Ramey, H.J. Jr.: “Wellbore Heat Transmission,” JPT (April 1962) 435 Trans AIME, No. 225.

Sagar, R.K., Dotty, D.R., and Schmidt, Z: “Predicting Temperature Profiles in a Flowing Well,” Paper SPE 19702 presented at 1989 SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Antonio, TX Oct.8 –11

Sharafutdinov, R.F. (2001): Multi-Front Phase Transitions During NonIsothermal Filtration of Live Paraffin-Base Crude. Bashkir State University, Russia, Ufa 450000, vol 42, No.2, 111-117

Shiu, K.C. and Beggs, H.D.: “Predicting Temperatures in Flowing Oil Wells,” J. Energy Resources Tech, (March 1989) 1- 11.

Valiullin, R.A, Sharafutdinov, R.F, Ramazanov, A.Sh., An Investigation of Thermodynamic Effects in Porous Media Saturated with Fluids. Bashkir State University, Russia, Ufa 450074