The Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This page is currently being maintained for archival purposes only. For the latest information, please visit us here.

Urban agriculture on the rise

A new study by Eric Lambin finds that the land in and around cities are increasingly becoming important centers of food production worldwide.

By

IWMI

International Water Management Institute

November 20, 2014

Eric Lambin (Photo: Tore Marklund)

Food production globally is taking on an increasingly urban flavor, according to a new study that finds 456 million hectares—an area about the size of the European Union—is under cultivation in and around the world’s cities, challenging the rural orientation of most agriculture research and development work.

“This is the first study to document the global scale of food production in and around urban settings and it is surprising to see how much the farm is definitely getting closer and closer to the table,” said Pay Drechsel, a scientist at the International Water Management Institute (IWMI) and co-author of the study, which was published in the November 2014 issue of the journal Environmental Research Letters.

The analysis, a collaboration between IWMI, under the CGIAR Research Program on Water Land and Ecosystems, the University of California-Berkeley, and Stanford University, is the first global assessment to quantify urban croplands and document the resources they consume, namely water, which has both environmental and food safety implications.

The authors said their goal was to highlight the role of urban farming in the quest for food security and sustainable development, given the largely rural focus of most agriculture research and policy work. In addition, they wanted to spotlight the starkly different view of urban farming one finds in the developed and developing world.

“We see this dichotomy where urban farming in wealthy countries is praised for reducing emissions and enhancing a green economy, while in developing countries, it can be regarded as an inconvenient vestige of rural life that stands in the way of modernization,” Drechsel said. “That’s an attitude that needs to change.”

According to Lambin, a co-author of the study, “The geographic boundary between urban and rural areas is more fuzzy than often assumed: within and around cities, one finds highly intensive forms of agriculture that benefit from the labor availability in cities and the close proximity to urban markets.”

Urban agriculture and food security

Drechsel and his colleagues note that urban agriculture, in addition to contributing to food security, puts marginal lands into productive use, assists in flood control, increases income opportunities for the poor and strengthens urban biodiversity.

Overall, the researchers found that 456 million hectares of land (about 1.1 billion acres) is being farmed in urban proximity. Most of that land lies just outside the city proper—within 20 kilometers—but 67 million hectares (about 166 million acres) is being farmed in open spaces in the urban core. These findings buttress previous studies documenting that up to 70 percent of households in developing countries are engaged in some type of farming and food production.

Related studies also have revealed that urban farms don’t typically grow “calorie rich” cereals like wheat or rice. Rather, they most often produce high-value and nutritionally important perishable crops like fresh vegetables. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, urban farmers supply up to 90 percent of the leafy salad greens consumed in the region’s rapidly growing cities.

“In urban areas of Ghana, everyday there are about 2,000 urban vegetable farmers supplying greens to 800,000 people,” Drechsel said. Moreover, most of these farmers irrigate their fields with highly polluted water, he said. In Accra, for example, up to ten percent of household wastewater is indirectly recycled by urban vegetable farms.

“These farms are now recycling more wastewater than local treatment plants,” Drechsel said.

Irrigation and water usage on urban farms

The study finds that within cities alone there are about 24 million hectares of land under irrigation, and 44 million hectares that are rain fed. Those numbers are larger than respective total area under rice in South Asia, the cultivated area under maize in sub-Saharan Africa, or the cultivated croplands of the cerrados and llanos in Latin America and the Caribbean. Going forward, the researchers note the prospect of “irrigated urban croplands playing a larger role in more densely populated and/or increasingly water scarce regions such as South Asia.”

The researchers observe that water usage by urban farms is not just a water recycling opportunity, it also can potentially become a food safety concern. For example, while irrigation allows consumers to get vegetables in the dry (lean) season, it also potentially exposes them to pathogens that can be present in the poorly treated water. But the researchers said the food safety issues, while important, can be addressed to maintain the many valuable and underappreciated contributions of urban farms.

A new portrait of urban farming

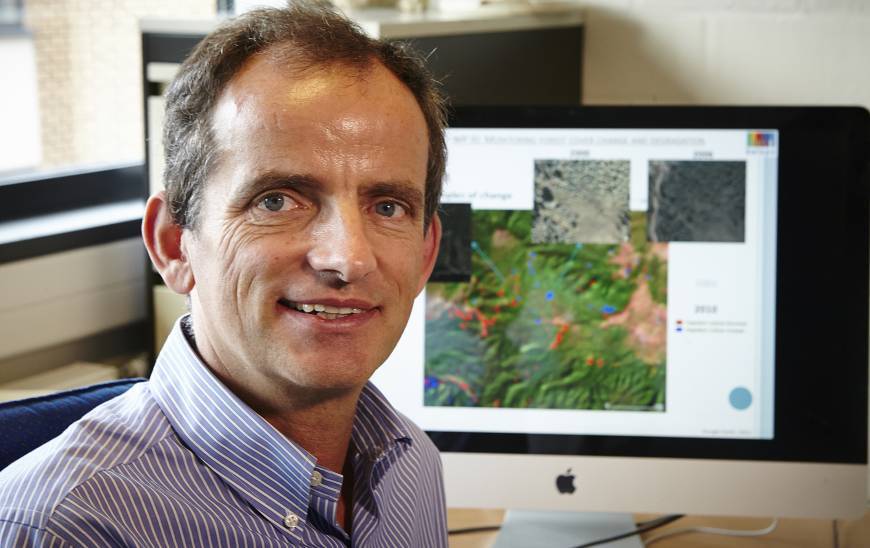

The richly detailed portrait of urban farming presented in the study was derived in part from new data and maps generated by researchers at the University of Frankfurt and at the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) that use satellite imagery and other sources to provider greater insights into the distribution of croplands globally. The authors say their study may have actually underestimated urban croplands, as they focused on farmed areas in and around cities with at least 50,000 residents, even though many countries define areas with smaller populations as “urban.”

“This is an important first step toward better understanding urban crop production at the global and regional scales,” said Anne Thebo, an environmental engineer at the University of California-Berkeley, who was the lead author of the study. “In particular, by including farmlands in areas just outside of cities we can begin to see what these croplands really mean for urban water management and food production.”

Researchers said further study is warranted exploring how crop production in and around cities affects ecosystem services in the rural-urban corridor and, in particular, what it means for managing water resources and improving food safety.

Research support was provided through the CGIAR Research Program on Water Land and Ecosystems, and through grants by USAID, Stanford University and the US Environmental Protection Agency.