The Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This page is currently being maintained for archival purposes only. For the latest information, please visit us here.

Listen: A conversation on teaching, tsunamis, and science nerdiness

By

Miles Traer

Stanford School Of Earth Sciences

July 30, 2014

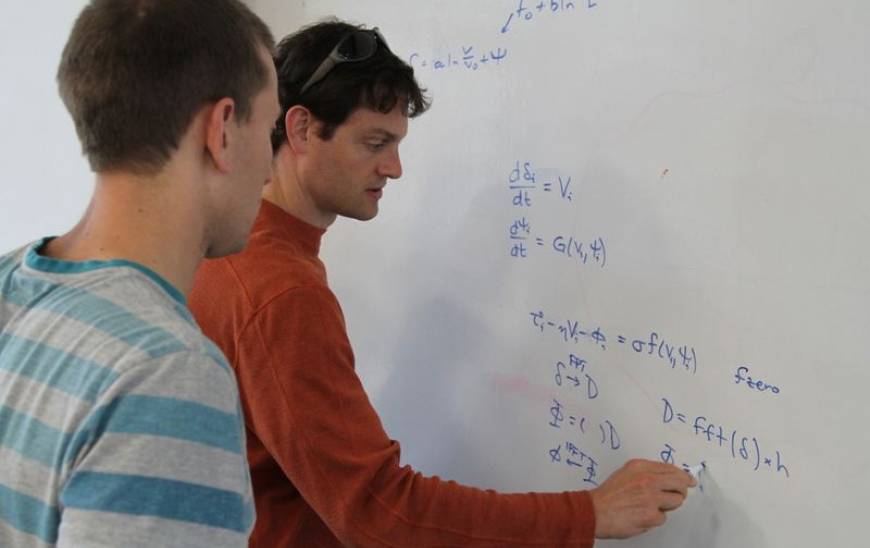

Assistant professor of Geophysics Eric Dunham (right) goes over some of the mathematics describing Earth processes with graduate student Brad Lipovsky. Dunham is the 2014 winner of the School of Earth Science's Excellence in Teaching Award.

Hello there. My name is Miles Traer and I am a scientist and science communications multimedia producer working at Stanford’s School of Earth Sciences. I received my B.A. in Geophysics from UC Berkeley and my Ph.D. in Geological and Environmental Sciences from Stanford University. Along with my friend and colleague Michael Osborne, I co-created the Generation Anthropocene podcast and I love telling stories about the odd, surprising, and awe-inspiring connections between humanity and Earth systems. I am an unabashed geoscience nerd who is constantly awed by the Earth, and awe-struck that we can figure any of this Earth science stuff out.

In early 2011, Eric Dunham, a geophysics professor, finished the fourth week of his popular Ice, Water, and Fire class teaching his students how to use basic physics to calculate the travel times of tsunami waves. Several weeks later, on the evening of March 11, 2011, a massive earthquake hit Tōhoku, Japan and his students put this knowledge to use.

It was a stunning coincidence. "That earthquake actually happened the evening prior to the final day of class," Dunham told me. "So instead of having the prepared lecture, we came in, we learned all that we could about the earthquake from the web, and we calculated the tsunami travel times." Shortly after class, the tsunami waves reached the Pacific coast of the US and the students learned that their calculated travel times were surprisingly accurate. "It was a really interesting way to close the class where the students saw that the skills they had gained could be put to really practical use," Dunham said.

Dunham researches earthquakes and volcanoes using mathematical models to describe the fundamental mechanical processes that drive these natural systems, and it’s a scientific approach he passes on to his students. His decision to toss out an entire lecture so that he and his students could investigate the earthquake and resulting tsunami using the skills they had learned just weeks earlier exemplifies why the School of Earth Sciences recently awarded Dunham with the excellence in teaching award. His students have praised him for his ability to take complex processes and make them tangible, for his insistence on using real-world examples to explain geophysical phenomena, and for his driving curiosity about the world around him.

I had the opportunity to sit down with Eric Dunham and talk about his approach to teaching, where his infectious enthusiasm for mathematics and physics comes from, and why all of his students rave about his unusual Oral Midterms. The audio of the interview is available through the player at the top of this page and a transcript of the interview is provided below.

Interview Transcript

Miles Traer: Recently you won the excellence in teaching award from the School of Earth Sciences. And from all of the nomination forms I could get my hands on, it seems like the students were really focused on one class: your Ice, Water, and Fire course. It seemed to be the most popular one. Can you briefly take us through that class and tell us what it covers?

Eric Dunham: Sure. We look at three different systems. We look at the ocean: water waves in the ocean, everything from the waves you see at the beach up to tsunamis. We look at the tides. And we move from there into volcanoes and the fluid mechanics of volcanic eruptions and magma flow beneath the surface. And we close with a look at the ice sheets and glaciers and how they flow. What we really do in the class is we learn the language of physics and mathematics and how to quantitatively describe these systems. And what we find is that all of these systems – there’s some fundamental physics that describe all of them.

MT: Are there any parts of the course that the students seem to pick up on right away?

ED: I think the example that really strikes them comes in the second week of class where we’ve set up the basics of water waves and then we take it to very long wavelengths that describe tsunamis. And suddenly, we make calculations that explain why the waves generated from the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake – the one in Japan that damaged the nuclear reactor there – why they had the amplitude that they did, why the waves were that high. Why did it take 15 minutes or so for the waves to reach the coast? And these things emerge from very basic principles that, in one or two classes, the students understand at some level and then all of a sudden, I can guide them through it in the lecture and we can draw some pictures, and I can ask, “how long will it take the waves to get there?” And they do a quick calculation themselves and they get the right answer.

That earthquake actually happened the evening prior to the final day of class one year, so instead of having the prepared lecture, we came in, we learned all that we could about the earthquake from the web, and we calculated the tsunami travel times. And sure enough, an hour or two after class ended, the waves came and hit Crescent City, hit Santa Cruz. So it was a really interesting way to close the class where the students saw that the skills they had gained could be put to really practical use.

MT: One of the things in your course that you do, and I’ve never heard of anyone doing outside of a language class, is an Oral Midterm. Can you describe what that is?

ED: It’s one of my favorite things to do. It is a 30-minute conversation with me: One on one, in my office. The students are at the blackboard writing out equations, drawing pictures, and talking about their understanding of different problems. So students pick up a set of questions – mainly conceptual in nature – about 30 minutes prior to the oral midterm, and then we get started. And it really is a conversation. So I pose certain questions to the students. Very quickly, as they start to respond, I can see and gauge their level of understanding. If they get hung up on something, I can give them a hint. I worry too much that in the written test taking form, if you just somehow have a mental block and get stuck on something you might not be able to proceed when really, you have the knowledge there. You just need a little bit of a push to unlock it. So in that oral midterm format, I can give them that little extra hint and that jogs their memory and then they can go forward. And it’s actually a fun experience. The students are often extremely nervous at the beginning, but then they realize how much they actually understand.

MT: Going back to these nominations, and just hearing you talk right now, one of the things that kept coming up was that, “this guy is clearly a physics nerd!” Where did you get hooked on physics? Everyone seems to have an appreciation for physics, but not everyone has that nerdy passion for it.

ED: I do have a passion for it! I spent a lot of time outside. I spent a lot of time hiking and backpacking and really just observing the natural world. I went to grad school in Santa Barbara so I spent a lot of time on the beach watching the ocean waves come in and watching streams interacting with the tides coming in and out. I just noticed things and was curious about, “why did it look like that?” Outside there were really spectacular clouds today, these periodic ripples of clouds in the sky. And to someone now trained as a physicist I immediately think, “there must be some kind of instability that’s setting a critical wavelength.” But I guess growing up, I would just see these things and I was curious about what it was that led to these really interesting natural phenomena. And the thing that was so appealing about physics was: from really just a few very basic principles, from that framework we can build out and suddenly have answers for why the world is working the way it’s working. And you don’t have to memorize thousands and millions of different molecules… I had problems with chemistry <laughs>… you know, I just love the simplicity of it, the elegance of it, I love the mathematics behind it – the language we use to quantify things – and then it was just so powerful to explain the behavior of the world.

MT: How did the “Geo” part of Geophysics enter your life?

ED: Coming out of undergrad I went to University of Virginia, where I was a physics major, I was really interested in the most fundamental of the fundamentals of physics; it was particle physics and string theory and such things. And in graduate school in Santa Barbara, as I was exploring that, I started to lose that conceptual understanding of it. And at the same time, I ended up taking a fluid mechanics class in engineering and suddenly it was this night and day contrast – all of the sudden I could visualize the system in the fluid class. I could understand what was happening. It felt very tangible.

MT: Do you remember that professor’s name by any chance?

ED: Ted Bennett was the one there. The other person that was extremely influential both as a scientist and as a teacher was Lars Bildsten. He’s a professor in physics at Santa Barbara – an astrophysicist – who taught a class informally known as “Stars with Lars,” and it was such a different style of thinking and problem solving than any I had encountered before. So instead of setting up these very rigorous initial boundary value problems and grinding through all the Bessel functions and spherical harmonics and such things to get some answer, he took a really complicated system – the star – and wrote down some equations. And then, instead of solving them exactly, he said, “ok, we only want this process balancing this one so we can develop this scaling relation.” And all of the basic physics was there. And it was just so eye opening. You know, suddenly you can make this approximation. It’s okay. Very quickly you realize that you can solve this huge class of problems that – sure the mathematics is formidable, and if you really want to solve it in full rigor you have to do it on a computer numerically and computationally – but that doesn’t mean you can’t get a lot of insight into that system and start to make sense of it. So I really learned from him that way of tackling problems. And it’s much the same type of skills that I try to teach in my Ice, Water, Fire class and in my other classes.

MT: So moving forward from here, it sounds like in every class that you teach you sort of throw in a new thing, a new element – maybe something you’re interested in or something your students are interested in. Do you have any ideas of how this class might evolve?

ED: Well, there are a lot of things that I’m personally curious about. I want to better understand the formation of the marine layer – the fog that drifts in and out here in the Bay Area that spills over the mountains. I want to understand that at this same very basic very intuitive level and really distill is down to a level that is accessible to a beginning undergraduate student with some background in physics. I want to bring in earthquakes. There are so many things that I’m not getting to teach at that undergraduate level that I’d really like to share with the students, and so it will probably mean creating new classes that cover these topics. It’ll give me the opportunity to learn it and share that learning process with the students.