The Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This page is currently being maintained for archival purposes only. For the latest information, please visit us here.

Global Warming and Extreme Weather Events

By

Louis Bergeron

April 8, 2013

Be it a “Snowpocalypse” blizzard or a “Frankenstorm” hurricane, a blistering heat wave or an extended drought, every extreme weather event these days prompts the same question: did global warming cause it?

Weather systems are too complex and variable for anyone to be able to answer that question. But scientists studying weather records from the last century have been working to tease out some overall trends from weather records with the goal of using that information to understand how global warming has – and will – affect the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events.

So how is that quest coming along?

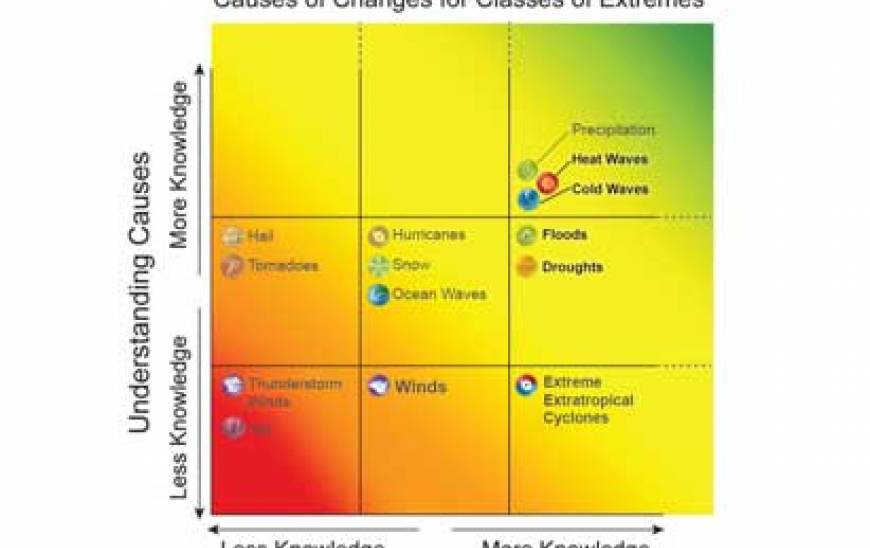

When it comes to heat waves, cold waves, floods and droughts, it’s going well, says Noah Diffenbaugh, who participated in a workshop in autumn 2012 that assessed those aspects of extreme weather. The workshop was convened by the National Climatic Data Center in support of the National Climate Assessment, and the results of the assessment have just been released in a peer-reviewed journal paper. Diffenbaugh is assistant professor in Environmental Earth System Science at Stanford University and center fellow in the Stanford Woods Institute for the Environment,

“The scientific community has a high level of understanding about what causes heat waves and cold waves in the current climate, as well as how those events are likely to respond to global warming,” he says. The causes of flooding and drought are not quite as well understood yet, but scientists are making progress on them.

More than two dozen leading scientists convened to evaluate the abundance and quality of available records of heat waves, cold waves, floods and droughts in the United States. They determined there are enough reliable data for each of those four phenomena for researchers to make reliable evaluations of whether the likelihood of those events has changed over time.

Diffenbaugh gave an invited presentation about his research group’s studies of severe heat and is one of the authors of a paper that came out of the workshop. The paper has been accepted for publication by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society and is available now.

The workshop was one of four held that brought together researchers who are at the forefront of their fields to evaluate the state of the science in various types of extreme weather events. The aim of the National Climate Assessment is to provide science to the nation and local communities to help them cope with changes wrought by global warming.

The papers produced in the workshops will contribute to the National Climate Assessment report that is required by an act of Congress to be presented to the President and the Congress every four years.

In addition to facilitating a discussion among a diverse group of scientists and informing the government on the state of climate change research, Diffenbaugh also sees another benefit from the workshop.

“Extreme events generate a lot of questions from people, but up until now, the scientific community hasn’t done such a systematic assessment of what’s been happening in the U.S. in terms of extreme weather,” he says.

“I think the assessment of the science produced by this workshop and the resulting peer-reviewed paper are very valuable for the public as it tries to understand how global warming interacts with this very complex climate system we live in.”