The Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences is now part of the Stanford Doerr School of Sustainability.

This page is currently being maintained for archival purposes only. For the latest information, please visit us here.

Finding order in the apparent randomness of Earth's evolving landscape

By

Miles Traer

<p>Stanford School Of Earth Sciences</p>

July 8, 2014

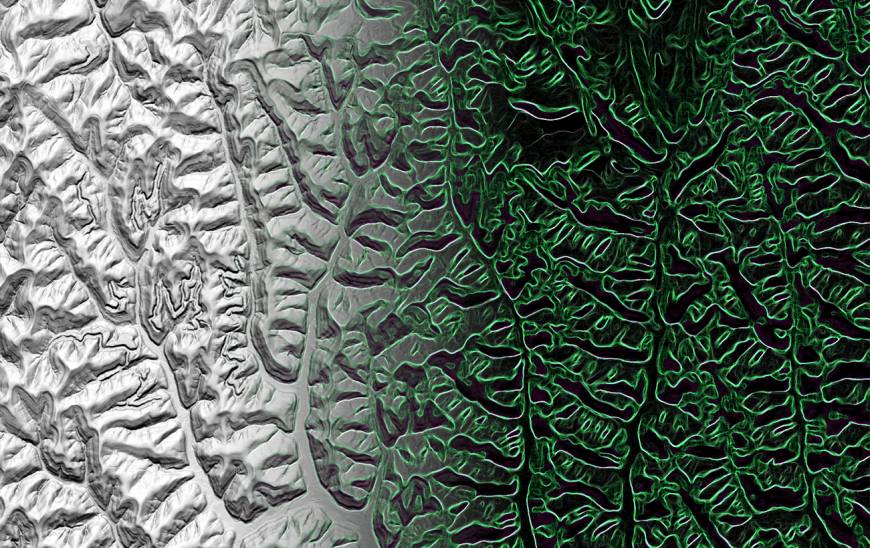

<p>Digitized landscape showing highlighted ridgelines (green) used to analyze the evolving surface.</p>

Cy Tolliver: "Maybe you could teach Leon a thing or two about shooting craps."

Silas Adams: "Yeah, right after I teach water how to run downhill."

This is an exchange between two characters in HBO’s Deadwood, set in the 1870s, and it might seem a strange starting point to discuss modern Earth science. Tolliver tries to lure Adams into playing a game of chance with his crooked dice man, Leon. Adams's sarcastic response comes from his recognition that the game is rigged, and teaching Leon about the odds of dice would be as useful as teaching water how to run downhill. The exchange is about order hidden within a façade of randomness - the cheat masquerading as an honest dice thrower - and it happens to reference water running downhill, a process that, until recently, scientists thought was as random as dice at a craps game.

Believe it or not, scientists’ understanding of the branched networks that form as water runs downhill hasn’t changed much since the timeframe of the show. Even modern techniques developed and employed since the 1960s cannot easily distinguish between channel networks generated randomly inside a computer and channels in the real world. But work by Stanford School of Earth Sciences recent PhD recipient Eitan Shelef and George Hilley, associate professor of Geological and Environmental Sciences, is beginning to shed light on this fundamental problem, and the tools they created might help link Earth-bound channels to channels on Mars and even the human circulatory system.

Shelef’s work, recently published in Geophysical Research Letters, challenges 50 years of research built on the assumption that the geometry of channel networks reflected a mathematically random process. Shelef and Hilley developed powerful mathematical relationships that captured not just the channel network’s geometry, but the geometry of the underlying landscape as well. Shelef, now a post-doctoral scholar at Los Alamos National Laboratory, explained that in these equations, they found a simple metric that distinguishes natural channel networks from those formed randomly within a computer, and in doing so, they firmly rejected the mathematically random hypothesis posed in the 1960s.

In rejecting this decades-old hypothesis, Shelef and Hilley can now extract invaluable three-dimensional data from two-dimensional images. “The way in which branched networks were measured in the past relied only on the two-dimensional map patterns of the channels in the networks,” said Hilley, a leading researcher on landscape evolution. Using high-resolution images captured with laser altimetry, the pair analyzed not only the channels, but the ridgelines as well. By incorporating information about the ridgelines separating the channels, Shelef and Hilley related channel network geometry to the two-dimensional signature left by three-dimensional erosion. Because different erosional processes leave different erosional signatures, which in turn affect channel patterns, Shelef and Hilley’s approach allows Earth scientists to infer the processes that erode the landscape simply by analyzing the overlying channel network.

Shelef expanded on this, pointing out that his mathematical tools can help decipher the processes that shape channel networks in areas in which scientists have good imagery, but limited elevation data, such as channel networks now buried underground, or channel networks on Mars or Saturn’s largest moon, Titan.

For example, images from NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter showed branched channel networks etched into the red planet’s surface. Images beamed back from the Huygens spacecraft as it landed Titan also showed channels likely formed from flowing liquid methane. Shelef’s research could help scientists better understand the processes acting on Titan today and the processes that carved out channel networks on Mars millions, if not billions, of years ago. “Channel networks are one of the most common and ubiquitous geometric forms found on the surface of this and some other planets,” Hilley said.

Branched networks on Mars (left), on Titan (center), and in the human circulatory system (right). (images courtesy of NASA/JPL and Wikipedia Commons)

The pair’s analysis of branched networks needn’t be limited to flowing liquids. Branched networks appear in life sciences as well, found in tree leaves and even the human circulatory system. With such ubiquity of branched networks, Shelef’s Earth science research might reach across disciplines. Understanding the processes that form branched biological networks could provide valuable scientific insights.

By seeing past the randomness inferred from previous research, Shelef and Hilley can better understand the processes that shape the world around us. Teaching water a thing or two about running downhill? Shelef and Hilley can do that, and quite a bit more.

Media Contact

Eitan Shelef, Los Alamos National Laboratory, 505-606-1641, shelef@lanl.gov

George Hilley, Stanford School of Earth Sciences, 650-723-2782, hilley@stanford.edu

Miles Traer, Stanford School of Earth Sciences, 650-497-9541, mtraer@stanford.edu